By Justin Jouvenal,

Jerry Givens executed 62 people.

Jerry Givens executed 62 people.

His routine and conviction never wavered. He’d shave the person’s head, lay his hand on the bald pate and ask for God’s forgiveness for the condemned. Then, he would strap the person into Virginia’s electric chair.

Givens was the state’s chief executioner for 17 years — at a time when the commonwealth put more people to death than any state besides Texas.

“If you knew going out there that raping and killing someone had the consequence of the death penalty, then why are you going to do it?” Givens asked. “I considered it suicide.”

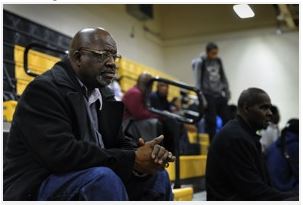

As Virginia executed its 110th person in the modern era last month, Givens prayed for the man, but also for an end to the death penalty. Since leaving his job in 1999, Givens has become one of the state’s most visible — and unlikely — opponents of capital punishment.

His evolution underscores that of Virginia itself and the nation. Although polls show that the majority of state residents still support the death penalty, Virginia has experienced a sea change on capital punishment in recent years that is part of a national trend.

The state has had fewer death sentences over the past five years than any period since the 1970s. Robert Gleason, who was put to death Jan. 16, was the first execution in a year and a half. As recently as 1999, the state put 13 to death in a single year.

Nationwide, the number of death sentences was at record lows in 2011 and 2012, down 75 percent since 1996, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Five states have outlawed capital punishment in the past five years, and Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley (D) affirmed plans to push for a moratorium there. Gallup polls show support for capital punishment ebbing.

Givens’s improbable journey to the death chamber and back did not come easily or quickly for the 60-year-old from Richmond. A searing murder spurred his interest in the work, but it was the innocent life he nearly took that led him to question the system. And he was changed for good when he found himself behind bars.

His story helps explain how a state closely associated with the death penalty for decades has entered a new era.

“From the 62 lives I took, I learned a lot,” Givens said.

The first execution

Friends and strangers regularly ask Givens the essential question: What is it like to take another man’s life? In answering, he vividly recalls his first execution, in 1984.

That it involved one of America’s most notorious killers helped solidify Givens’s feelings then that the death penalty was just.

Linwood Briley was one of three brothers in a gang responsible for one of the bloodiest murder sprees — and death row escapes — in state history.

The day before Briley’s execution, Givens said, the death row team began a standard 24-hour vigil, monitoring Briley at the now-shuttered Virginia State Penitentiary in Richmond. The goal, as Givens put it, was to keep the condemned from killing himself before the state could.

Nevertheless, the first execution took a toll. Givens said the most difficult part of that execution — or any other — was something he called the “transformation.”